This article was published in TSE science magazine, TSE Mag. It is part of the Autumn 2025 issue, dedicated to finance and money. Discover the full PDF here and email us for a printed copy or your feedback on the mag, there.

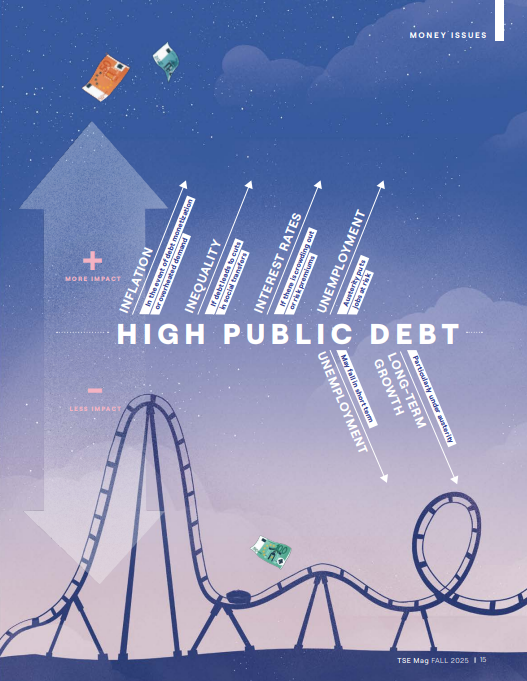

As the global debt burden reaches historic highs, can governments keep borrowing without going under? Drawing on official statistics and econometric techniques, Fabrice Collard and Patrick Fève build models to explore how debt interacts with growth, interest rates, and economic shocks. In this interview, they explain that debt brings risks, but it’s not inherently reckless.

Why do we borrow?

We borrow to finance our needs, when we want to study, buy a car, or buy a home. Businesses also need to borrow to carry out their activities.

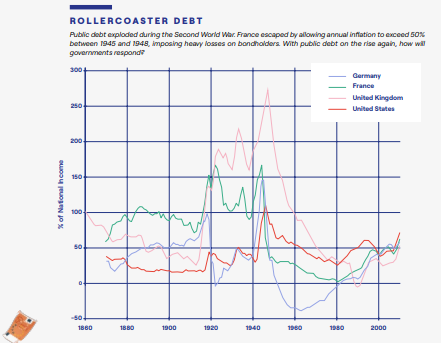

States must take out loans if tax revenues do not match expenditure. This public debt helps to smooth spending over time, and to cope with crises such as Covid-19 or recessions. It ensures the continuity of public services, and payment of social transfers like unemployment benefits and pensions, which also act as stabilizers in times of volatility.

Is public debt harmful?

Balanced budgets every year are rare – they can be harmful. Instead of repaying debt, most governments only pay interest on existing debt. Some take on new debt to pay off existing debt, but this can become a dangerous game.

It’s important to consider the long-term aims and behavior of the borrower. Debt can be beneficial if used to finance investments – such as infrastructure, education, and green energy – that support growth and productivity.

The economic context also has a huge influence. For example, rising debt is sustainable as long as it is outpaced by the economy, so that growth and tax revenues remain higher than interest rates. However, societies with weak growth will struggle to manage soaring debt without structural reforms.

Currency is another important factor. When countries with weak currencies take on debt in dollars, they may be forced to mobilize more resources to pay the interest due.

What happens when countries can’t afford debt payments?

A debt crisis can occur when countries default, failing to meet their obligations. Governments can then be excluded from the financial market, triggering recession and potentially lead to social unrest, as in Greece in the 2010s. In such cases, the International Monetary Fund may propose a rescue plan.

Is debt a burden for future generations?

Inevitably, yes. But this burden can be lightened if debt is used to finance projects for the future. It's not just a question of finance, but about how investments and projects improve the well-being of future generations.

Has France borrowed too much?

It's not so much the absolute level of debt that's worrying, but the pace at which it increases and the way it's managed. A debt-to-GDP ratio of over 110% is high by historical standards, but France is partly protected by the Euro and the European Central Bank. The cost of this stability is that France cannot devalue its currency to lighten its burden, and faces scrutiny by markets and European partners. If debt rises too fast, or if it mainly finances recurrent expenditure with no lasting effect on growth, confidence can quickly deteriorate.